Questions About Paul's Letter to the Galatians

Answers to common questions asked about introductory issues concerning Paul's letter to the Galatians including its date and destination.

What are some indications that Galatians has exerted enormous influence on Christianity?

The early church fathers wrote more commentaries on Galatians than on any other book in the New Testament.[1] Martin Luther, who described it as being as dear to him as his own precious wife, called it "my own epistle, to which I have plighted my troth (i.e pledged my truthfulness)."[2]

Galatians has been described by George Duncan as the "magna carta of Evangelical Christianity." It is an exposition of the doctrine of justification. It addresses the Spirit's transforming work in the life of the believer, Christ's substitutionary atonement, and a high Christology. This epistle teaches salvation is offered entirely by God's grace and serves as "a theological refutation of a heresy that, if accepted, would have destroyed the whole church." Galatians remains the fiercest and clearest dismissal of salvation through human effort from the pen of the apostle Paul.[3]

What are the two possible destinations for Galatians?

- North Galatian Theory: The term Galatia could be used in the ethnic sense to describe the area by Gauls or Celts. If this is the sense Paul had intended, he was writing to churches in northern Galatia (Ancyra, Pessinus, and Tavium).

- South Galatian Theory: If Paul was writing to the Roman province of Galatia, he was writing to churches in southern Galatia. This Roman province included Antioch of Pisidia, Iconium, Lystra, and Derbe.

What is the support for each of these possibilities?

Support for the North Galatian Theory

- View of the early church fathers and Protestant reformers, J.B. Lightfoot (19th century), and J. Moffatt (early 20th century).[4]

- Luke's usage of the term Galatia in Acts 16:6 and 18:23 and distinguishing Galatia from Phrygia (a regional district but not a province) suggests that Luke was referring to the Galatian district excluding the districts of Pisidia and Lycaonia. In Acts 13:13–14 and 14:6, Luke identified locations based on geographical regions rather than Roman provinces.[5]

- No strong evidence Paul had faced strong opposition in the church of South Galatia.

- Paul wrote to the church at Colossae even though he never visited their church.

Support for the South Galatian Theory

- There is no biblical evidence that Paul ever visited the North Galtian cities, while Acts records Paul planting churches in South Galatia. Paul knew the Galatian readers personally (Gal 1:8; 4:11–15; 19).

- Reference to the Galatian churches in 1 Corinthians 16:1 references the Galatian churchs as being among the contributors to the collection for Jerusalem. In Acts 20:4, two south Galatians appear to represent the churches presenting the gift.[6]

- Barnabas, mentioned in Galatians 2, supports South Galatia as the destination since Barnabas only accompanied Paul on his first missionary journey through cities in South Galatia.

- The route described in Acts 16:6 and 18:23 seems to be a South Galatian route.

- "Galatia" was the only word that would have encompassed Antioch, Lystra, Iconium, and Derbe.[7]

- Paul normally used Roman imperial names for provinces.[8]

How are the destination and the dating of Galatians interrelated?

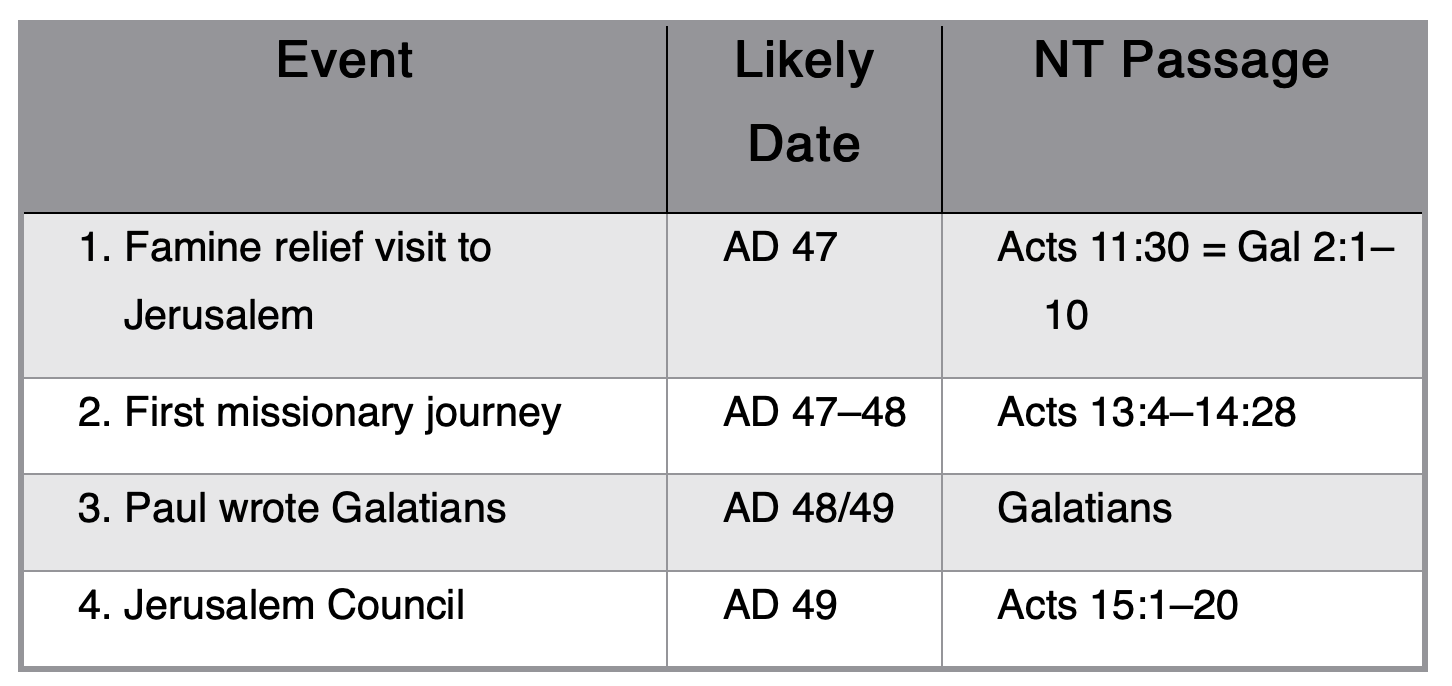

The determination of destination makes the greatest difference in date. The South Galatian theory affirms an early date, either shortly after Paul's first missionary journey or just before or shortly after the Jerusalem council. The North Galatian theory typically affirms a later date (AD 53–57), usually during Paul's third missionary journey.

Moises Silva does favor a South Galatian theory but argued for a later date.[9]

Was Galatians written before or after the Jerusalem Council? What evidence supports this claim?

Internal evidence is stronger for a Pre-Jerusalem Council Date (AD 48–49).

Post-Jerusalem Council Date

Identification of the Jerusalem visit of Galatians 2:1–10 with the Jerusalem Council recorded in Acts 15:1–20.

- These two records include the same four participants: Paul, Barnabas, Peter, and James.

- They debated the same issue on the obligation of Christians to keep the Jewish law.

- They led to the same outcome: circumcision should not be imposed on Gentile converts, but the converts should remember the poor.

- There is no mention of any conference with the apostles during the famine relief in Acts, so equating Galatians 2:1–10 and Acts 11:30 is based on an argument of silence.

Pre-Jerusalem Council Date

The visit of Galatians 2:1–10 corresponds with Acts 11:28–30.

- Part of the purpose of the famine relief offering is to demonstrate the Gentiles' authentic confession of the gospel and to inspire the Jerusalem church to accept the Gentile converts (2 Cor 9:12–14).

- Equating the Galatians 2:1–10 visit with the Jerusalem council necessitates that Paul omitted and neglected to mention one of his visits to Jerusalem in the book of Galatians. Since Paul states that his apostleship was divine and not derived from the apostles in Jerusalem, Paul must account for every visit to Jerusalem (Gal 1:20).

- If the Jerusalem Council had already taken place, Paul's appeal to its decree would have strengthened Paul's argument against the Judaizers.

- Peter's hesitancy about table fellowship with Gentiles (Gal 2:12) makes more sense before the Jerusalem Council.

- Galatians 2:1–10 describes a private conference. Acts 15 describes a public event.

- Paul referred to visiting Syria and Cilicia between his visits to Jerusalem. If the second visit is to the Jerusalem Council, then Galatia should be added to Syria and Cilicia. But since Paul visited Syria and Cilicia before the famine relief visit, and Paul's first missionary journey occurred afterward, the specific mention of Syria and Cilicia supports Galatians 2:1–10 corresponding with Acts 11:28–30, which supports a pre-Jerusalem Council date.[10]

What was Paul's primary purpose in writing Galatians?

Assuming the South Galatian theory, Paul begins his evangelistic efforts in the churches of South Galatia as recorded in Acts 13–14. The Jews opposed Paul's work, and the issue of salvation by grace alone versus the law of Moses was the crux that divided Christian disciples from Galatian Jews.

Soon after Paul had left, false teachers infiltrated the church and preached a different gospel. They insisted that keeping the Mosaic law (the main focus was circumcision) was essential to salvation. These false teachers (called "Judaizers" by scholars) were likely Jews who called themselves Christians.

Paul's primary purpose in writing Galatians was to defend the gospel and oppose the teaching that circumcision was necessary for salvation. Because Paul was so clear on this teaching while he was with the churches at Galatia, to require circumcision for salvation was to reject Paul's apostleship. So, while Paul's primary purpose was to defend the gospel of justification by faith alone and combat the false gospel of the Judaizers, his secondary purpose was to defend his apostolic authority, which was also being attacked. Paul also wrote to clarify that the true Christian gospel does NOT justify immoral or unethical behavior. Paul describes Christians filled with the Holy Spirit will live a life consistent with the law's righteous demands.

Why did Paul rebuke the Galatians?

Paul rebukes the Galatians for abandoning the one true gospel and accepting the Judaizers' claim that circumcision is necessary for salvation.

What did Paul teach in Galatians concerning justification by faith versus works of the law?

Paul taught that a person is justified by faith apart from the works of the law. In Galatians 2:15–16 and 3:6–14, Paul explains that sinners are declared righteous by God through faith in Christ rather than by personal acts of obedience. The righteousness that qualifies an individual to pass the scrutiny of divine judgment is an alien righteousness imputed to the believer on the basis of his faith.

But in recent years, scholars like James Dunn and N.T. Wright have attacked this traditional understanding of Paul's teaching. They argue that "justification" is not the imputation of God's righteousness to the believer but is actually an anticipation of God's final judgment of the individual which involves an examination of the totality of the believer's life and not simply dependent upon a profession of faith.

Dunn has argued that "works of the law" refers to the deeds prescribed by the Torah (circumcision, Sabbath keeping, and observance of purity laws distinguishing Jews from Gentiles). Therefore, he understood the false gospel in Galatia was not attempting to earn salvation through moral achievement but rather the teaching that one must become a Jew in order to be saved.

However, Paul's citation of Deuteronomy 27:26 in Galatians 3:10 suggests that fulfilling every element of the law ("works of the law") in order to evade the curse of the law was the false teaching Paul had in mind.

So in summary, "Paul teaches that believers are declared righteous by God, both now and in eschatological judgment, based on Christ's sacrifice and in response to their faith in Jesus and not through obedience to the Old Testament law."[11]

What contributions to the canon does Galatians make?

Galatians makes clear that Gentiles are on equal terms with Jews in the church, and in contrary to the "false gospel" of the Judaizers, circumcision is not required. Using the example of Abraham, Galatians confirms that justification is by faith alone, apart from the works of the law. The book of Galatians defends the Christian's freedom and liberty from the demands of the law. Galatians also teaches much about the life of the Spirit and the fruit of the Spirit.

CA. B. Cousar, Galatians, Interpretation (Atlanta, GA: John Knox, 1982), 1. ↩︎

G. W. Hansen, "Galatians, Letter to the," in Dictionary of Paul and His Letters, ed. G. F. Hawthorne, R. P. Mrtin, and D. G. Reid (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1993), 323. ↩︎

Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, and Charles L. Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament, 2nd ed (Nashville, TN: B & H Publishing Group, 2016), 483. ↩ ↩︎

Köstenberger, Kellum, and Quarles, 488–489. ↩︎

J. Moffett, An Introduction to the Literature of the New Testament, 3rd ed. (Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 1918), 93. ↩︎

Köstenberger, Kellum, and Quarles, 490. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

F.F. Bruce, Commentary on Galatians (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1982), 15. ↩︎

M. Silva, Exploration in Exegetical Method: Galatians as a Test Case (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1996), 129–139. ↩︎

Köstenberger, Kellum, and Quarles, 494. ↩︎

Köstenberger, Kellum, and Quarles, 501-503. ↩︎